![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

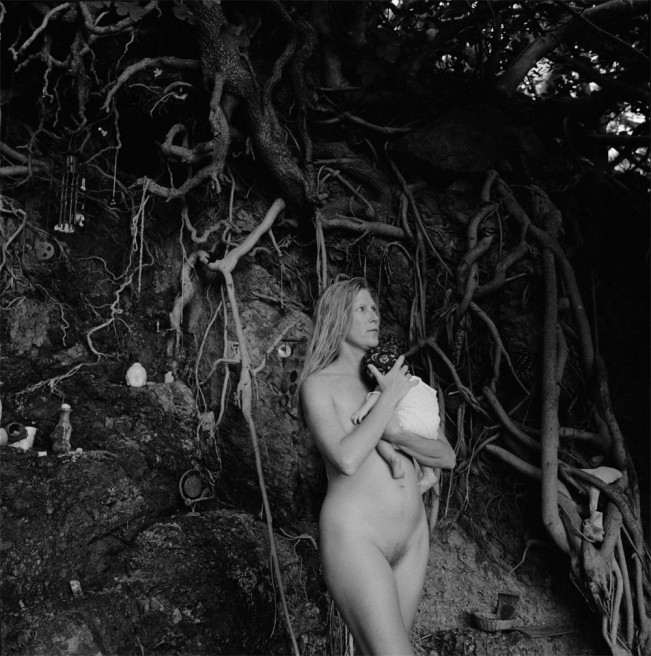

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

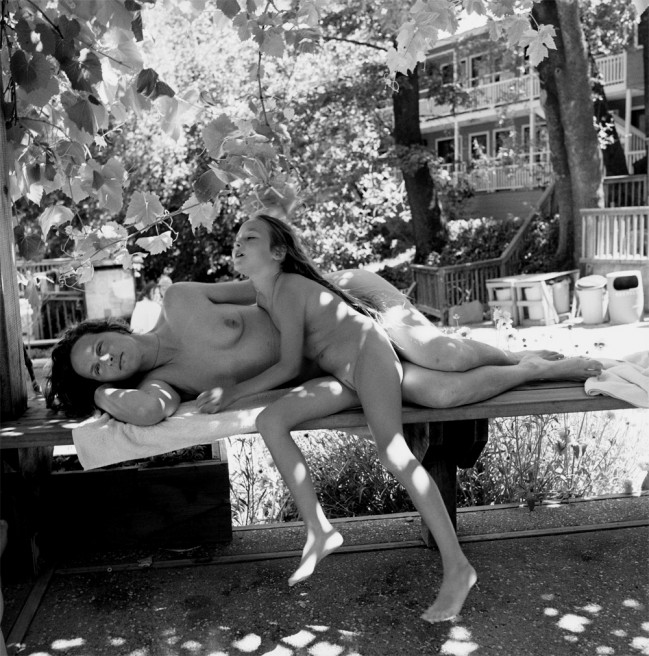

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

![Enamored - Photo by Lauren Greenfield]()

Photo by Lauren Greenfield

—Henry Horenstein

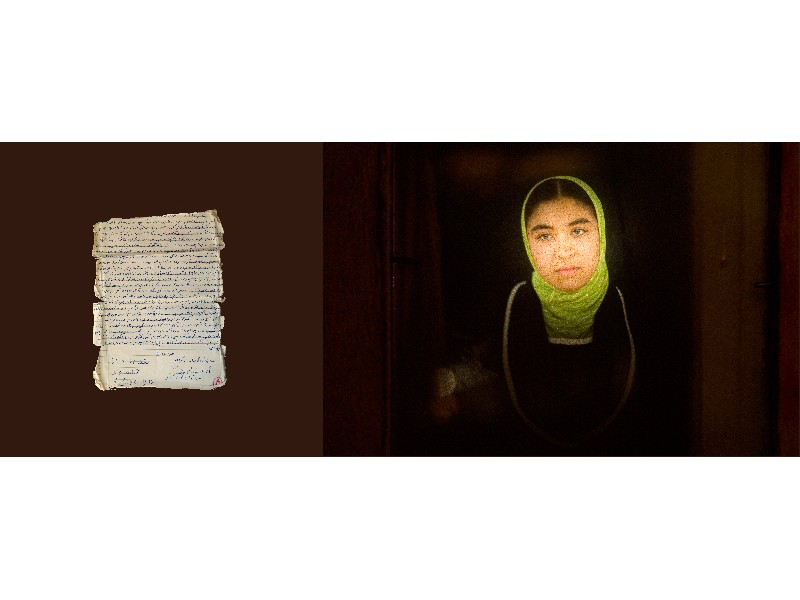

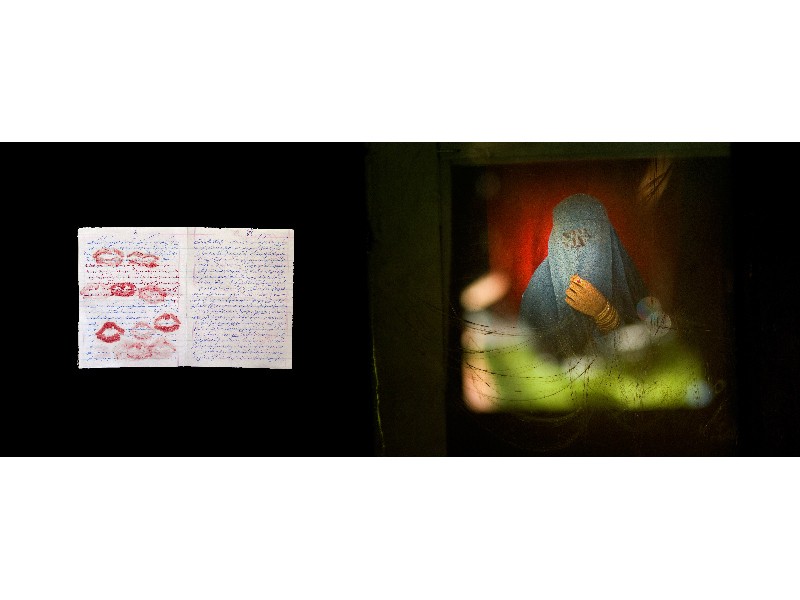

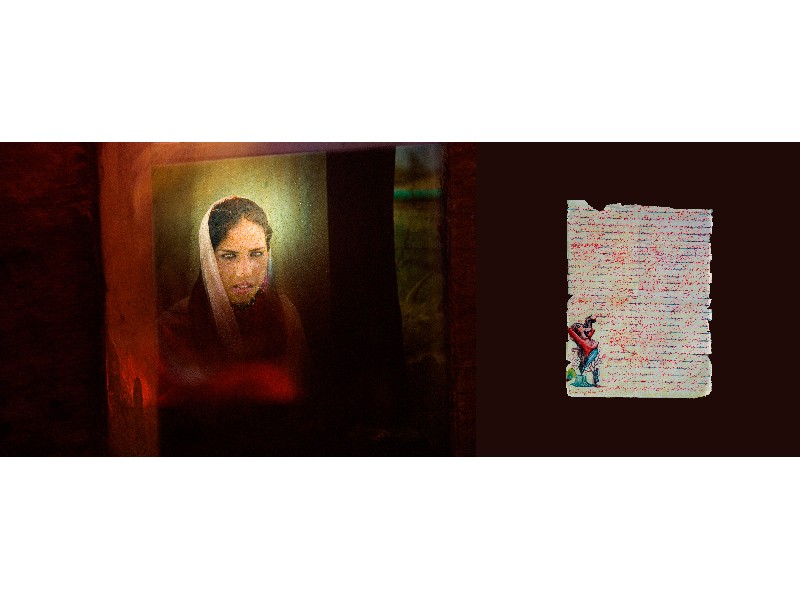

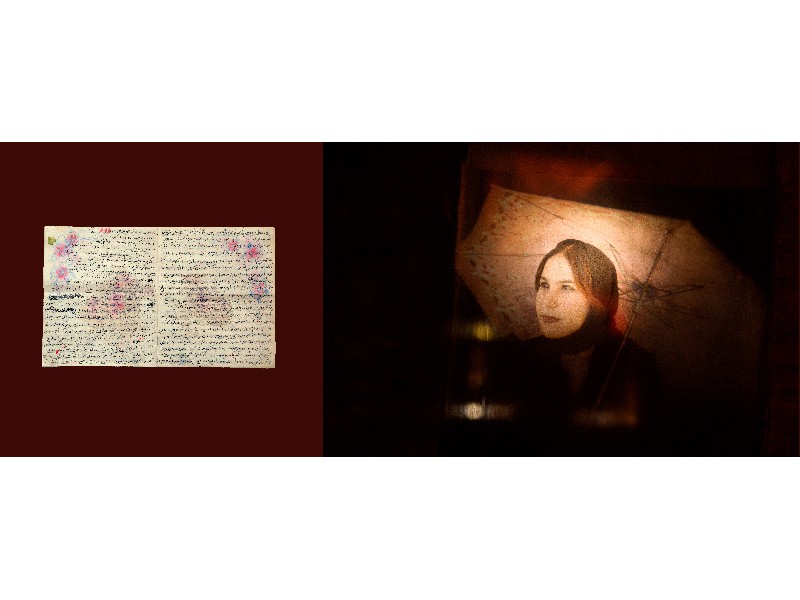

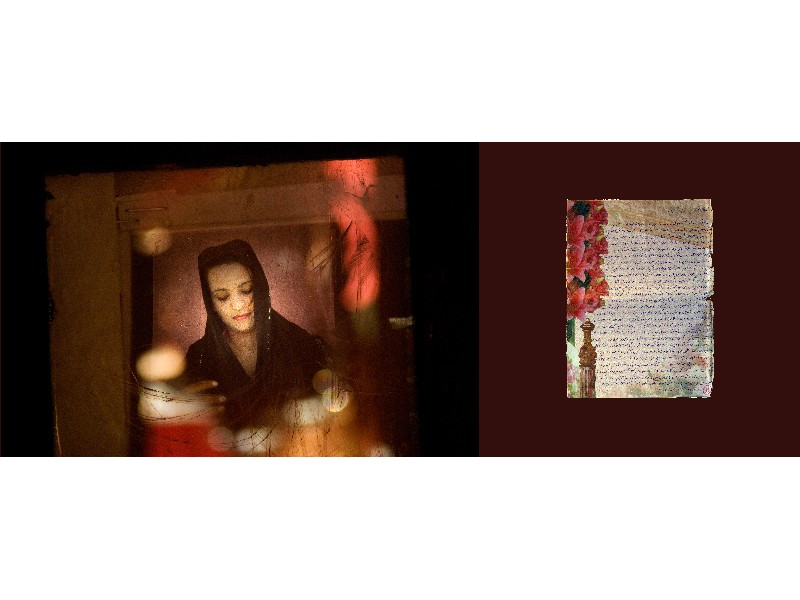

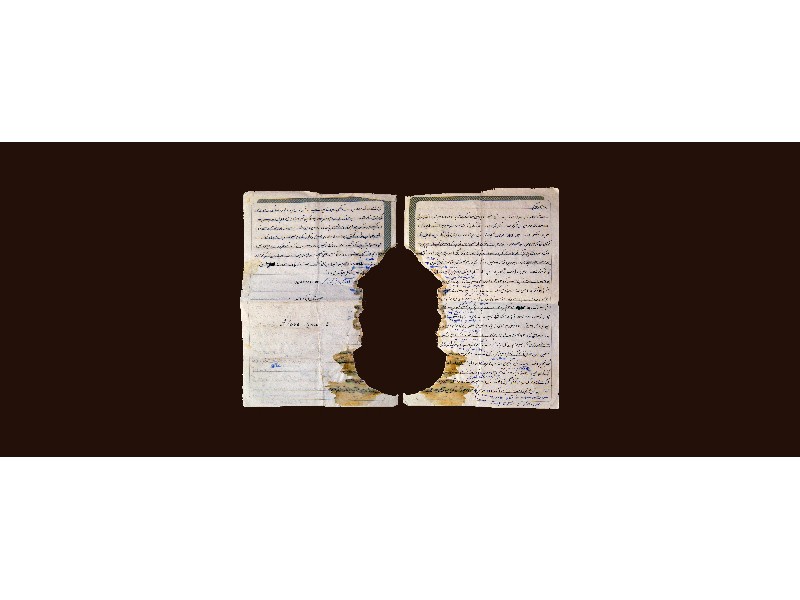

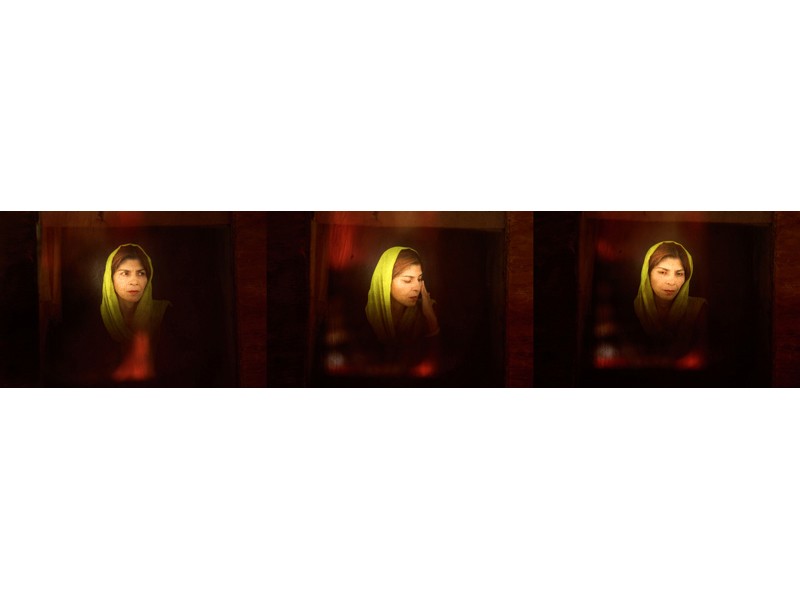

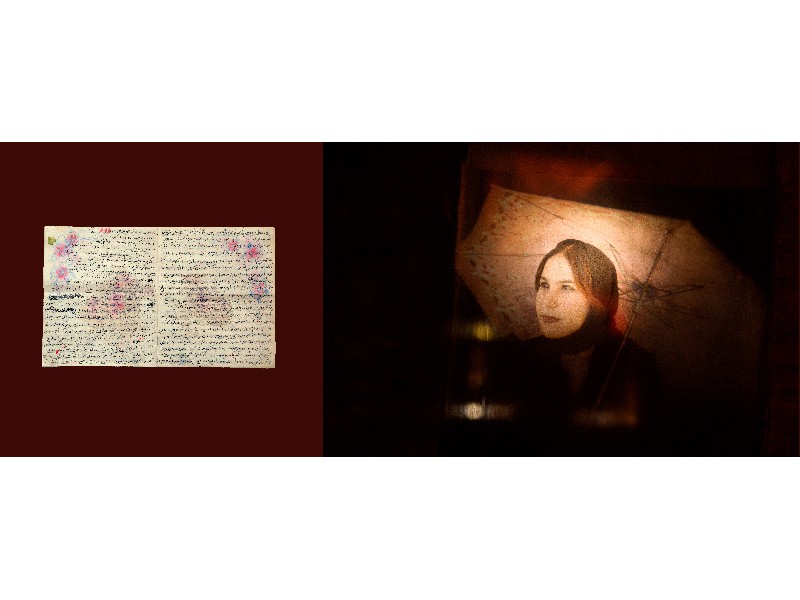

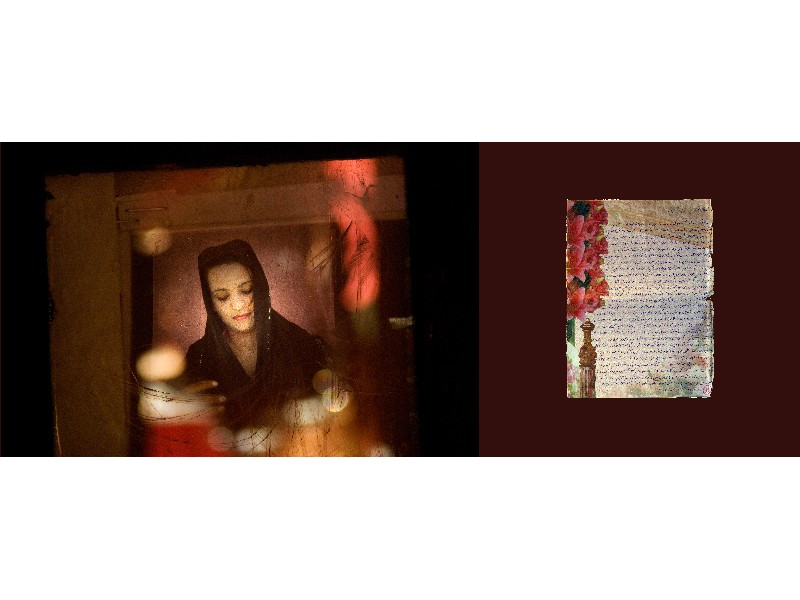

“There is no room for love in Afghanistan,” said a young teenage girl as we sipped tea in the sitting room of her family’s Kabul apartment. She said this as if it were true, had been for years, for as long as she could remember. Not in that moment, but in the twilight of that evening and for several years after, her remark caused me to reflect on the kind of space that love can consume. An endless space without dimension, like a sketch without charcoal or a raindrop without water - more space than even the glorious mountains of the Hindu Kush could ever take up. Yet in the tiny precipice of this Afghan girl’s heart, where love and all of its beautiful unknowns should have blossomed; it didn’t, it couldn’t.

The love that I felt in Afghanistan was a luxury. It was a luxury because I was an outsider and could afford to let Afghanistan enter me, enter me in a way that allowed me to recognize the beauty in all of its harshnesses. And although this land and its strife often, almost every day, brought me to feel defeat, loss, and compassion, I always had a great fluffy cushion to land on--a cushion provided to me by the love of my family and the memories of a life monumentally different to what I was a witness to there. From the moment I landed in Kabul, that love could have gone in several directions. It could have rested on the landscape, the children, or the poetry that existed in the tired sighs of the people. But I was unequivocally drawn - as one is to light in utter darkness - to Afghan women.

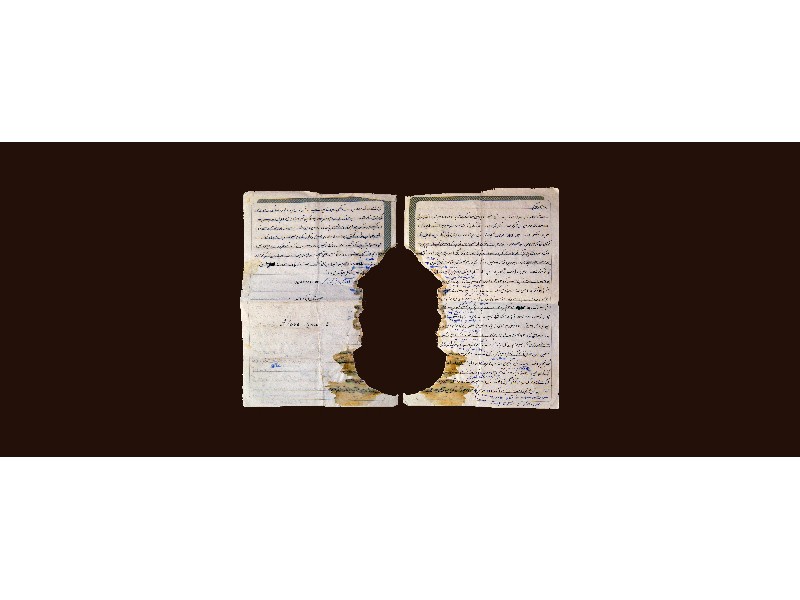

For these women, I had passion and energy, my emotions had no boundaries. For them I gave in wholeheartedly in order to show them to others as I saw them for myself; the most intricately designed butterflies stripped of their wings. And then one day, a surprise, a young man I had known brought to me a stack of letters; more than six hundred pages. It was a secret correspondence of love, one that allowed the imaginations of him and his love to wander, for it was only in those pages and in their dreams that they could walk together. To disclose their love would mean the end of their relationship and perhaps worse. That day I realized that love existed in Afghanistan - in a single glance, a certain tone, the shadow of a schoolyard - but not without grave risk and consequence.

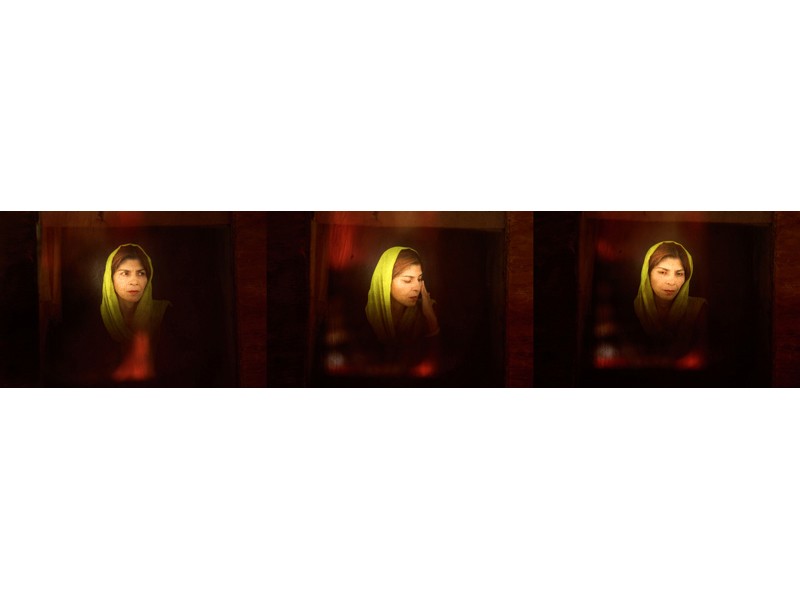

For me, this complicated intertwining of love took shape and form in the darkness of an old Afghan box camera. It was there as I peered into a space no larger than a small treasure chest, isolated from the rest of Afghanistan, that I could fully express how I felt for these women.

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

![Enamored - Photo by Henry Horenstein]()

Photo by Henry Horenstein

—Edith Maybin

The Tenby Document: In these photographs, Edith Maybin investigates the space between mother and daughter. She takes portraits in a home environment where she and her daughter enact secret stories together whist wearing Marks and Spencer undergarments, a gesture towards Maybin’s own mother, and an investigation into female rituals and sentimental inheritance. These secret stories then replay until the camera captures the mother and daughter separately in the same position. This allows for digital reassembly and the final presentation of the two as one.

Maybin digitally places her five-year-old daughter’s head on her own body; the photograph resolving the dichotomy of the relationship. In closing the gap between mother and daughter these images, whilst formal, subversively provide room for fantasy, identity reversal, and reversed escape. Inspired by Lady Clementina Hawarden’s photographic tableaux of her daughters, Maybin and daughter paradoxically elude the gaze by way of imaginative abstraction into a place, like Vermeer’s women, intangible. The Conversion Document: In this body of work Edith Maybin investigates the threshold between consciousness and dreaming, an enigmatic place full of mystery and magic.

Within her home, Maybin constructs a stage, a fantastic platform, where over the cycle of a week she photographs her daughter sleeping. The innocence of childhood dress-up games are visited as Maybin enters the photograph wearing outfits chosen by her daughter the night before. Inspired by the presence of catastrophe and awe found in Caravaggio’s “The Conversion of Saint Paul” and Bernini’s “Ecstasy of St. Teresa” Maybin continues her study of the mother/daughter bond.

—Andrea Bruce

The Daughters of Iraq are mostly women who have been widowed by the violence of the past five years. Hired by Sunni officials, they provide security at checkpoints and use the income to support their families. In their villages this job is the only socially acceptable way for widows to earn an income, keeping them from prostitution and desperation.

The "Daughters of Iraq" were created by Iraqi neighborhoods to employ women whose husbands died in the violence of the Iraq war. Their dangerous jobs involved searching women at checkpoints at a time when female suicide bombers were common. Women holding normal jobs are shunned in most village cultures, but these jobs, the local government said, were acceptable. In 2009 the program to support the Daughters ran out of funds. Since then, many widows have turned to prostitution and homelessness. I took their portraits at checkpoints while they told the story of their husband's death and the struggle to survive without a man to support them. Lacking childcare, several took their children to work with them.

![Enamored - Thikra Abed Douad, 30, has four children. Her husband was...]()

Thikra Abed Douad, 30, has four children. Her husband was kidnapped on...

READ ON

Thikra Abed Douad, 30, has four children. Her husband was kidnapped on October 17, 2007, and was never heard from again. It is believed he was targeted because he was Shiite. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Badria Siwan Hussein, 41, has seven children. Her husband...]()

Badria Siwan Hussein, 41, has seven children. Her husband was kidnaped in...

READ ON

Badria Siwan Hussein, 41, has seven children. Her husband was kidnaped in October of 2007 and never seen again. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Shela Hassan Elwan, 34, has six children. Her husband was...]()

Shela Hassan Elwan, 34, has six children. Her husband was kidnapped on June...

READ ON

Shela Hassan Elwan, 34, has six children. Her husband was kidnapped on June 4, 2006, when driving a delivery truck to Baghdad. His body was never found. She was pregnant with their youngest son when he disappeared. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Dunia Ahmed Salmon, 23, has one six-year-old boy. Her...]()

Dunia Ahmed Salmon, 23, has one six-year-old boy. Her husband disappeared on...

READ ON

Dunia Ahmed Salmon, 23, has one six-year-old boy. Her husband disappeared on July 9, 2006. His body has not been found. "I tell my son his father will still come home," she said. "I can't tell him his father is dead." Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Iptisan Abbas Muhammed, 41, has four children. Her...]()

Iptisan Abbas Muhammed, 41, has four children. Her husband was killed in a...

READ ON

Iptisan Abbas Muhammed, 41, has four children. Her husband was killed in a suicide bombing on December 18, 2007, while he was sitting in a coffee shop in Diyala province. Her 18-year-old son was also handicapped by the bombing. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Fawzia Salah Abbas, 34, stands with her youngest child...]()

Fawzia Salah Abbas, 34, stands with her youngest child Tiba Moufez Abed, 5,...

READ ON

Fawzia Salah Abbas, 34, stands with her youngest child Tiba Moufez Abed, 5, who often accompanies Fawzia to work at checkpoints. Fawzia's oldest son died in a suicide bombing in December of 2007. Her husband was kidnapped on February 19, 2006, & never seen again. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Nathar Jassam Kassim, 29, is married to a man who had his...]()

Nathar Jassam Kassim, 29, is married to a man who had his leg amputated due...

READ ON

Nathar Jassam Kassim, 29, is married to a man who had his leg amputated due to a stray bullet wound. Mobile-only in a wheelchair, he has been unable to provide for their family. Against his will, Nathar works as a Daughter of Iraq to support them. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Ridiya Mahmoud Haddam, 37, holds her only child Tabariq...]()

Ridiya Mahmoud Haddam, 37, holds her only child Tabariq Waad Mi Zahem, 3. Her...

READ ON

Ridiya Mahmoud Haddam, 37, holds her only child Tabariq Waad Mi Zahem, 3. Her husband was kidnapped and beheaded in 2005 when her daughter was 2 months old. She has since struggled to provide for her family. "You can see how poor I am, I am working in this risky job only for my daughter," she said. Photo by Andrea Bruce

![Enamored - Wonsa Hamad Alwan, 41, has six children. Her husband was...]()

Wonsa Hamad Alwan, 41, has six children. Her husband was killed in an IED...

READ ON

Wonsa Hamad Alwan, 41, has six children. Her husband was killed in an IED explosion on June 22, 2006. Photo by Andrea Bruce

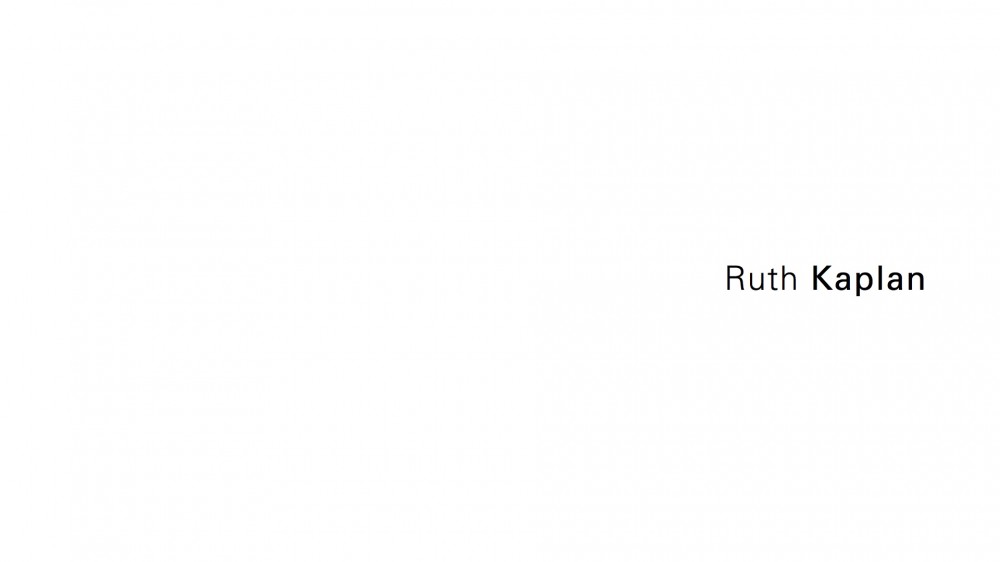

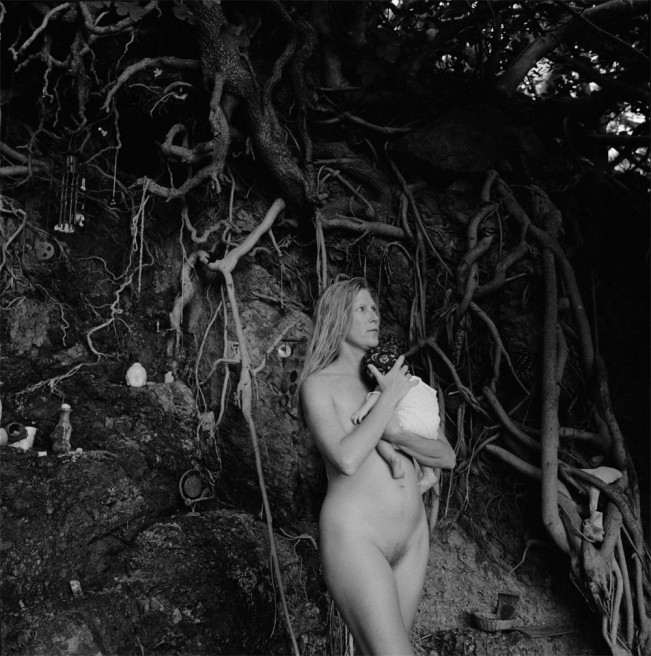

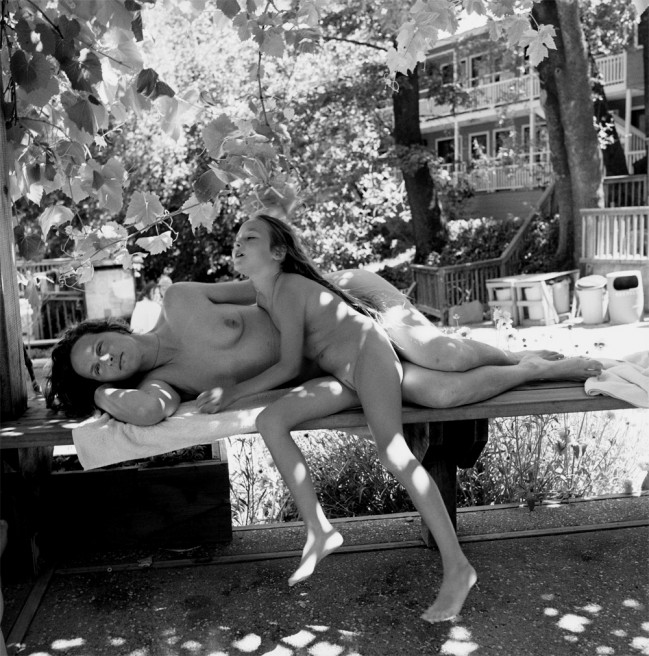

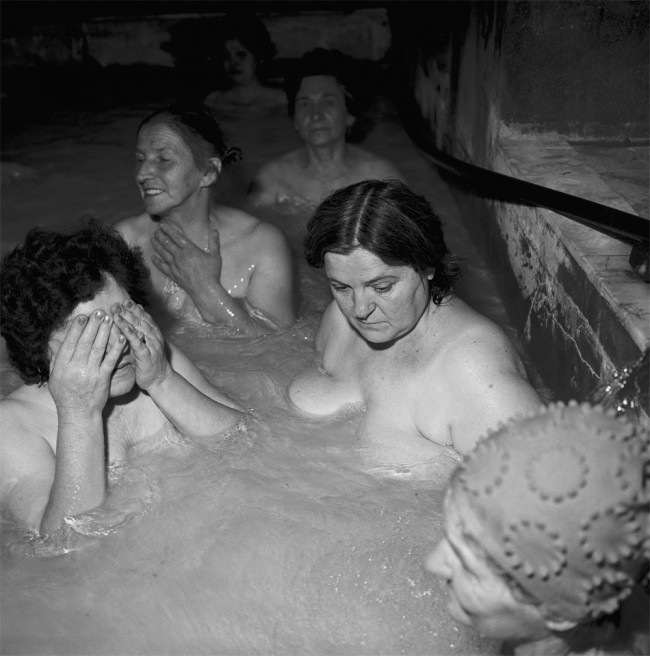

—Ruth Kaplan

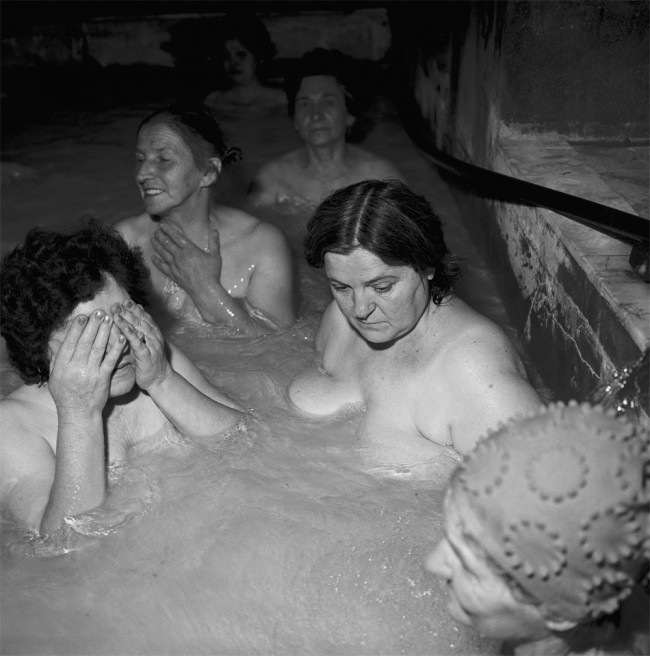

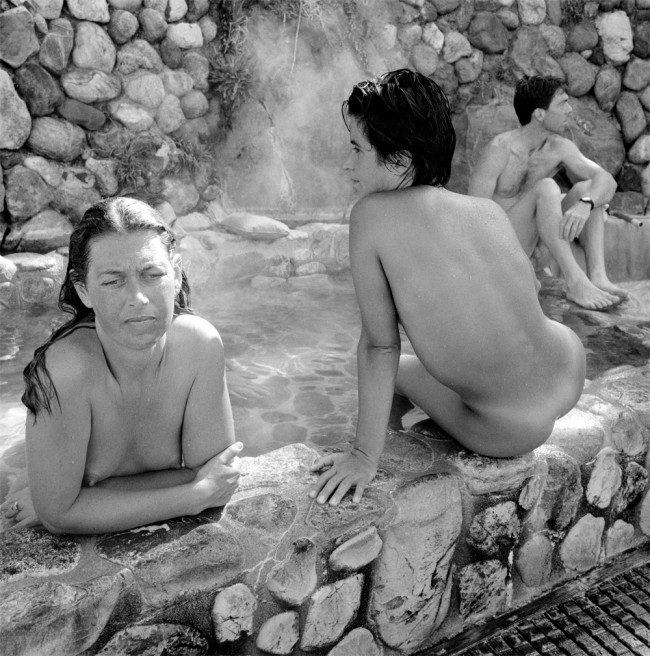

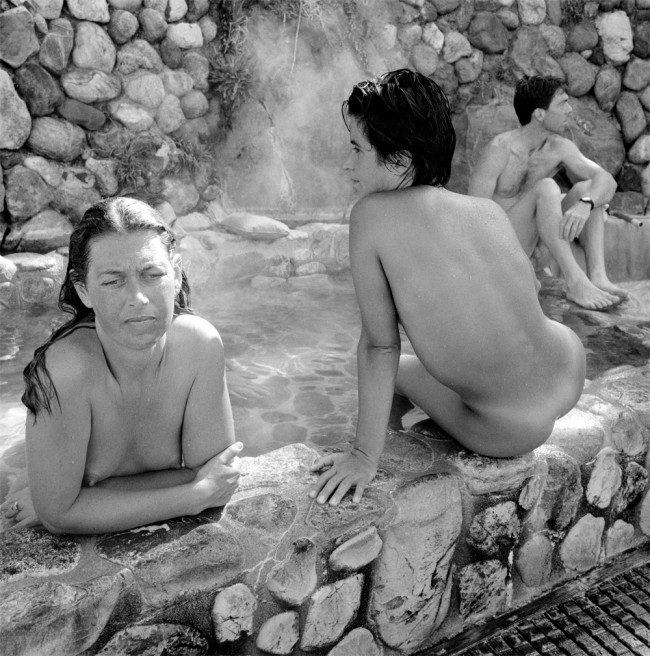

The bathers inhabit a netherworld between the visceral and the imagined. One begins to merge with the large formlessness. The waters drew me close, like any seduction, but not uncritically. From 1991 to 2002 I photographed in hot springs and bathhouses in California, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, Iceland, and Morocco.

As both voyeur and participant, I was able to document these rituals of purification within a world often considered private, with its unique social bonding amidst decaying architecture of striking landscape. Attitudes to the body vary culturally, especially in regards to gender. How one inhabits one’s body is influenced by the prevailing sociopolitical stance whether one is aware of it or not. The participants present themselves with the subtle distinctions of the larger politic, sometimes with a sense of entitled place and self-acceptance, other times in rebellion, other times with an inexhaustible drive to alter oneself.

Attitudes toward media changed dramatically through this project, which originated in an analog world when the Internet was not yet widespread. The technological onslaught that ensued brought us youtube and cellphone cameras. Concerns about privacy are not so abstract anymore. In a way, this project represents that time just before. It would certainly be difficult to do now. However, the lure of the waters remains. The players go back, again and again, to share in sensuality, decadence, healing, transformation, and absolution as evidence of the body’s yearning towards Eden in a technological age, towards immersion and experience.

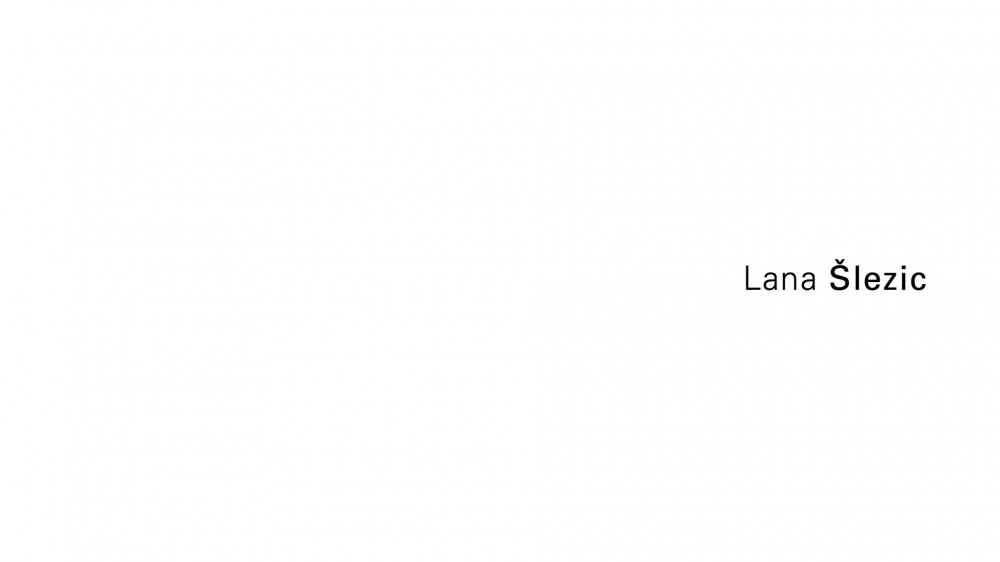

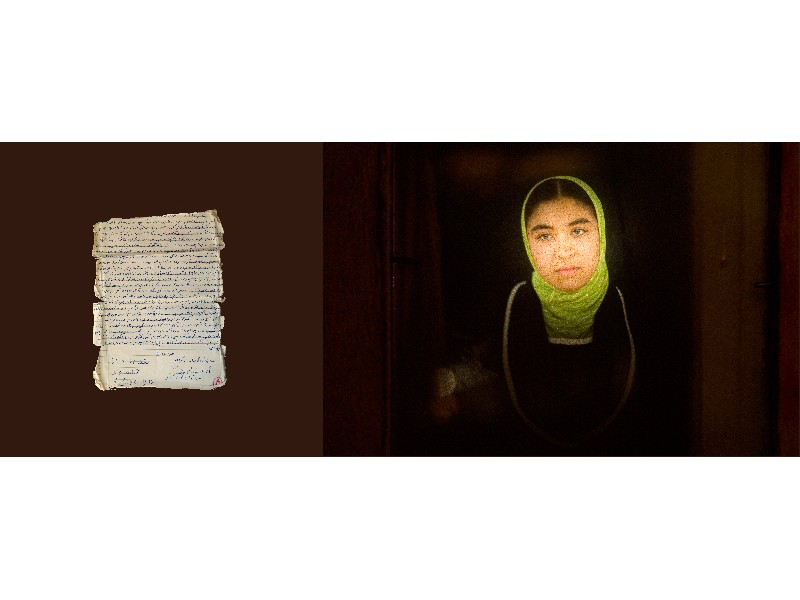

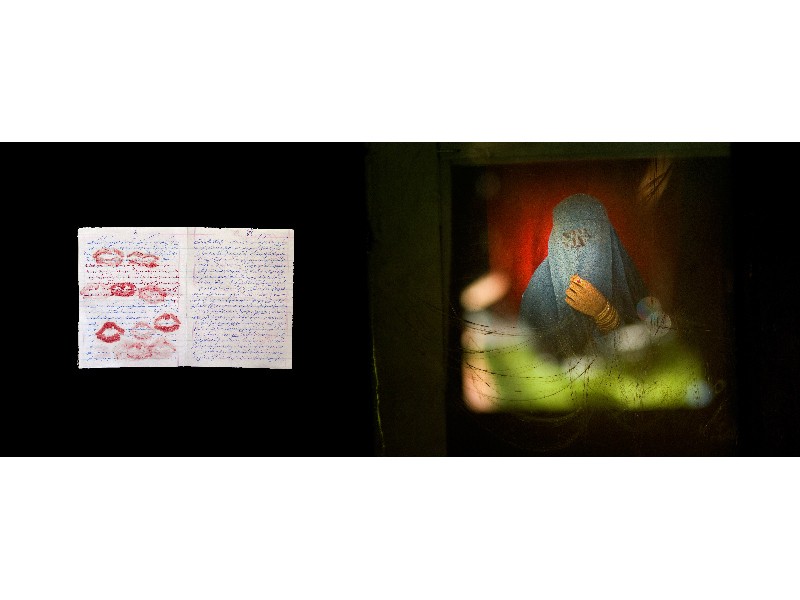

—Lana Slezic

“There is no room for love in Afghanistan,” said a young teenage girl as we sipped tea in the sitting room of her family’s Kabul apartment. She said this as if it were true, had been for years, for as long as she could remember. Not in that moment, but in the twilight of that evening and for several years after, her remark caused me to reflect on the kind of space that love can consume. An endless space without dimension, like a sketch without charcoal or a raindrop without water - more space than even the glorious mountains of the Hindu Kush could ever take up. Yet in the tiny precipice of this Afghan girl’s heart, where love and all of its beautiful unknowns should have blossomed; it didn’t, it couldn’t.

The love that I felt in Afghanistan was a luxury. It was a luxury because I was an outsider and could afford to let Afghanistan enter me, enter me in a way that allowed me to recognize the beauty in all of its harshnesses. And although this land and its strife often, almost every day, brought me to feel defeat, loss, and compassion, I always had a great fluffy cushion to land on--a cushion provided to me by the love of my family and the memories of a life monumentally different to what I was a witness to there. From the moment I landed in Kabul, that love could have gone in several directions. It could have rested on the landscape, the children, or the poetry that existed in the tired sighs of the people. But I was unequivocally drawn - as one is to light in utter darkness - to Afghan women.

For these women, I had passion and energy, my emotions had no boundaries. For them I gave in wholeheartedly in order to show them to others as I saw them for myself; the most intricately designed butterflies stripped of their wings. And then one day, a surprise, a young man I had known brought to me a stack of letters; more than six hundred pages. It was a secret correspondence of love, one that allowed the imaginations of him and his love to wander, for it was only in those pages and in their dreams that they could walk together. To disclose their love would mean the end of their relationship and perhaps worse. That day I realized that love existed in Afghanistan - in a single glance, a certain tone, the shadow of a schoolyard - but not without grave risk and consequence.

For me, this complicated intertwining of love took shape and form in the darkness of an old Afghan box camera. It was there as I peered into a space no larger than a small treasure chest, isolated from the rest of Afghanistan, that I could fully express how I felt for all of this woman.

Enamored

Curated by Adriana Teresa Letorney, FotoVisura

GuatePhoto Festival 2010

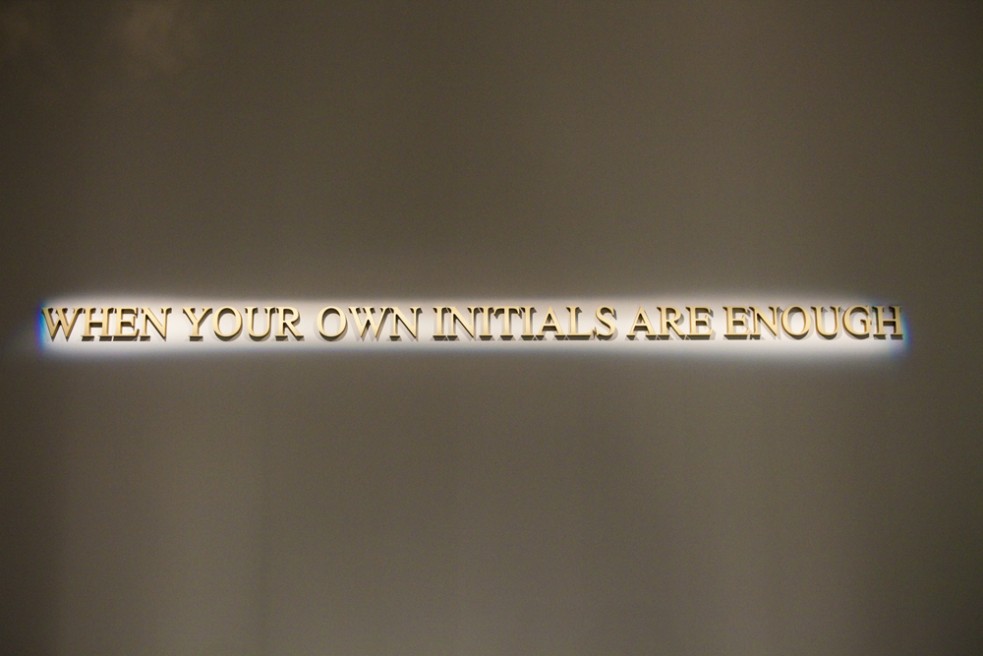

Enamored is a visual reflection about the force within women which binds our strength with our passion, intelligence with our body and healing power through belief; the internal energy that makes us courageous and victorious, without retaliation. On the contrary, it is a force, inspired by love, that is revealed in our silence.

This exhibit addresses the innate inner strength in women, one that unites us worldwide; transcending social, cultural and economical barriers. The fiber of the feminine within. The inner spirit. The energy that crucifies and crowns. The radiance that inspires with love when one is enamored.

This photographic exhibition seeks to let this intangible force become tangible, at least for an instant. Maybe this visualization will inspire change.

Location: Carlos Mérida Museum of Modern Art, Guatemala City

—Henry Horenstein

“There is no room for love in Afghanistan,” said a young teenage girl as we sipped tea in the sitting room of her family’s Kabul apartment. She said this as if it were true, had been for years, for as long as she could remember. Not in that moment, but in the twilight of that evening and for several years after, her remark caused me to reflect on the kind of space that love can consume. An endless space without dimension, like a sketch without charcoal or a raindrop without water - more space than even the glorious mountains of the Hindu Kush could ever take up. Yet in the tiny precipice of this Afghan girl’s heart, where love and all of its beautiful unknowns should have blossomed; it didn’t, it couldn’t.

The love that I felt in Afghanistan was a luxury. It was a luxury because I was an outsider and could afford to let Afghanistan enter me, enter me in a way that allowed me to recognize the beauty in all of its harshnesses. And although this land and its strife often, almost every day, brought me to feel defeat, loss, and compassion, I always had a great fluffy cushion to land on--a cushion provided to me by the love of my family and the memories of a life monumentally different to what I was a witness to there. From the moment I landed in Kabul, that love could have gone in several directions. It could have rested on the landscape, the children, or the poetry that existed in the tired sighs of the people. But I was unequivocally drawn - as one is to light in utter darkness - to Afghan women.

For these women, I had passion and energy, my emotions had no boundaries. For them I gave in wholeheartedly in order to show them to others as I saw them for myself; the most intricately designed butterflies stripped of their wings. And then one day, a surprise, a young man I had known brought to me a stack of letters; more than six hundred pages. It was a secret correspondence of love, one that allowed the imaginations of him and his love to wander, for it was only in those pages and in their dreams that they could walk together. To disclose their love would mean the end of their relationship and perhaps worse. That day I realized that love existed in Afghanistan - in a single glance, a certain tone, the shadow of a schoolyard - but not without grave risk and consequence.

For me, this complicated intertwining of love took shape and form in the darkness of an old Afghan box camera. It was there as I peered into a space no larger than a small treasure chest, isolated from the rest of Afghanistan, that I could fully express how I felt for these women.

—Edith Maybin

The Tenby Document: In these photographs, Edith Maybin investigates the space between mother and daughter. She takes portraits in a home environment where she and her daughter enact secret stories together whist wearing Marks and Spencer undergarments, a gesture towards Maybin’s own mother, and an investigation into female rituals and sentimental inheritance. These secret stories then replay until the camera captures the mother and daughter separately in the same position. This allows for digital reassembly and the final presentation of the two as one.

Maybin digitally places her five-year-old daughter’s head on her own body; the photograph resolving the dichotomy of the relationship. In closing the gap between mother and daughter these images, whilst formal, subversively provide room for fantasy, identity reversal, and reversed escape. Inspired by Lady Clementina Hawarden’s photographic tableaux of her daughters, Maybin and daughter paradoxically elude the gaze by way of imaginative abstraction into a place, like Vermeer’s women, intangible. The Conversion Document: In this body of work Edith Maybin investigates the threshold between consciousness and dreaming, an enigmatic place full of mystery and magic.

Within her home, Maybin constructs a stage, a fantastic platform, where over the cycle of a week she photographs her daughter sleeping. The innocence of childhood dress-up games are visited as Maybin enters the photograph wearing outfits chosen by her daughter the night before. Inspired by the presence of catastrophe and awe found in Caravaggio’s “The Conversion of Saint Paul” and Bernini’s “Ecstasy of St. Teresa” Maybin continues her study of the mother/daughter bond.

—Andrea Bruce

The Daughters of Iraq are mostly women who have been widowed by the violence of the past five years. Hired by Sunni officials, they provide security at checkpoints and use the income to support their families. In their villages this job is the only socially acceptable way for widows to earn an income, keeping them from prostitution and desperation.

The "Daughters of Iraq" were created by Iraqi neighborhoods to employ women whose husbands died in the violence of the Iraq war. Their dangerous jobs involved searching women at checkpoints at a time when female suicide bombers were common. Women holding normal jobs are shunned in most village cultures, but these jobs, the local government said, were acceptable. In 2009 the program to support the Daughters ran out of funds. Since then, many widows have turned to prostitution and homelessness. I took their portraits at checkpoints while they told the story of their husband's death and the struggle to survive without a man to support them. Lacking childcare, several took their children to work with them.

—Ruth Kaplan

The bathers inhabit a netherworld between the visceral and the imagined. One begins to merge with the large formlessness. The waters drew me close, like any seduction, but not uncritically. From 1991 to 2002 I photographed in hot springs and bathhouses in California, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, Iceland, and Morocco.

As both voyeur and participant, I was able to document these rituals of purification within a world often considered private, with its unique social bonding amidst decaying architecture of striking landscape. Attitudes to the body vary culturally, especially in regards to gender. How one inhabits one’s body is influenced by the prevailing sociopolitical stance whether one is aware of it or not. The participants present themselves with the subtle distinctions of the larger politic, sometimes with a sense of entitled place and self-acceptance, other times in rebellion, other times with an inexhaustible drive to alter oneself.

Attitudes toward media changed dramatically through this project, which originated in an analog world when the Internet was not yet widespread. The technological onslaught that ensued brought us youtube and cellphone cameras. Concerns about privacy are not so abstract anymore. In a way, this project represents that time just before. It would certainly be difficult to do now. However, the lure of the waters remains. The players go back, again and again, to share in sensuality, decadence, healing, transformation, and absolution as evidence of the body’s yearning towards Eden in a technological age, towards immersion and experience.

—Lana Slezic

“There is no room for love in Afghanistan,” said a young teenage girl as we sipped tea in the sitting room of her family’s Kabul apartment. She said this as if it were true, had been for years, for as long as she could remember. Not in that moment, but in the twilight of that evening and for several years after, her remark caused me to reflect on the kind of space that love can consume. An endless space without dimension, like a sketch without charcoal or a raindrop without water - more space than even the glorious mountains of the Hindu Kush could ever take up. Yet in the tiny precipice of this Afghan girl’s heart, where love and all of its beautiful unknowns should have blossomed; it didn’t, it couldn’t.

The love that I felt in Afghanistan was a luxury. It was a luxury because I was an outsider and could afford to let Afghanistan enter me, enter me in a way that allowed me to recognize the beauty in all of its harshnesses. And although this land and its strife often, almost every day, brought me to feel defeat, loss, and compassion, I always had a great fluffy cushion to land on--a cushion provided to me by the love of my family and the memories of a life monumentally different to what I was a witness to there. From the moment I landed in Kabul, that love could have gone in several directions. It could have rested on the landscape, the children, or the poetry that existed in the tired sighs of the people. But I was unequivocally drawn - as one is to light in utter darkness - to Afghan women.

For these women, I had passion and energy, my emotions had no boundaries. For them I gave in wholeheartedly in order to show them to others as I saw them for myself; the most intricately designed butterflies stripped of their wings. And then one day, a surprise, a young man I had known brought to me a stack of letters; more than six hundred pages. It was a secret correspondence of love, one that allowed the imaginations of him and his love to wander, for it was only in those pages and in their dreams that they could walk together. To disclose their love would mean the end of their relationship and perhaps worse. That day I realized that love existed in Afghanistan - in a single glance, a certain tone, the shadow of a schoolyard - but not without grave risk and consequence.

For me, this complicated intertwining of love took shape and form in the darkness of an old Afghan box camera. It was there as I peered into a space no larger than a small treasure chest, isolated from the rest of Afghanistan, that I could fully express how I felt for all of this woman.